History of the Davids-Garrison/Jug Tavern Property

Heather Jane McCormick

April 9, 2005

A Report for the Long Range Planning Committee,

Jug Tavern of Sparta, Inc

The remnants of the “Old Garrison House” at Sparta have been demolished during the past week. The structure was built before the Revolution and has always been one of the features of the history of the days of our grandparents. Although the edifice has been left to rack and ruin for some years past, some of the timbers are quite sound, and the old-fashioned split lath are in prime condition.

“An Old Landmark Gone”

Democratic Register, 6 September 1884

In 1986, when Greta Cornell, director of the Ossining Historical Society, discovered the account in an old Ossining newspaper of the demolition of the “Old Garrison House,” it laid to rest a persistent local tradition that Sparta’s “Jug Tavern” was one of the area’s earliest buildings. Today, period maps and a complicated paper trail of deeds for the Jug Tavern property tell us that it was indeed owned and occupied by members of the Garrison family for most of the nineteenth century, but in 1884 many readers of the Democratic Register would have remembered the family, particularly the elderly widow Annis Garrison, who had owned the property with her husband Nathaniel before 1814 and lived there until her death in 1869. In the Sparta of 1884 almost everyone would have known immediately what was meant by the “Old Garrison House.”

It is striking that in the years between 1884 and the 1920s and 30s, when local histories and especially newspaper stories began to promote the colonial and Revolutionary history of the Jug Tavern, the memory of the property’s rebirth was forgotten, or perhaps suppressed in favor of a more romantic and venerable past until the real story was forgotten. Today, understanding the history of the site is complicated not only by the complex and fragmentary history of the property’s ownership, but also by the tenacity of colorful, but undocumented and often questionable, local lore, which includes a popular story that George Washington or Major John Andre made stops at the property’s well, a claim that the cellar was used to hold captured British soldiers, and even one account that maintained that Washington did stop for a drink on the property, but that it was in the tavern not at the well![1] Such stories flourished and sometimes gathered new details well into the second half of the twentieth century. One local resident with an interest in the history of the property told a newspaper reporter in 1975 that her research confirmed that locals “bought herbal medicines from Mrs. Garrison, the wife of the tavern keeper[,] who rented the place from Lord Philipse, and [sold] thread which she bought in New York City, walking both ways . . . sometimes through British lines.”[2]

One bit of lore that persists even today has to do with the name of the property, which has been popularly known as the Jug Tavern for years due to a story that “liquor was sold by the jug and not retailed by the glass” there, “on the honor of word,” or illicitly, in the eighteenth century.[3] The story seems to have been established well before the name “Jug Tavern” came into use, although some said the name had been used during the Revolution. It is significant, for instance, that in the 1884 account of the demolition of the Garrison house, the name “Jug Tavern” is not mentioned. Indeed, in 1976 Frank A. Vanderlip, Jr., son of Frank and Narcissa Vanderlip who rebuilt much of Sparta in the first quarter of the twentieth century, questioned the name. Writing to Marion Cormier and Greta Cornell to thank them for a copy of “A Walking Tour of Sparta” they had sent, he explained

In my about 60-year knowledge of Sparta, I never heard the Inn spoken of as the “Jug Tavern.” I always remember its being called the “Grapevine Inn,” and it had grape vines hung around the front second-story porch. On page 17, you say that no record exists of the “Jug Tavern” having a liquor license. Perhaps this is because that was not the name of the place at that time. Look up “Grapevine Inn.”[4]

A survey of newspaper and other accounts of the property published into the 1930s confirms Vanderlip’s statement. The name “Jug Tavern” it seems, was not in popular use until the 1940s. Its earliest use identified to date occurs in an 1947 unpublished manuscript based on an interview with the elderly local historian, Helena May Foster, who explains that the building “is known as the Old Post Road Jug Tavern” [author’s emphasis], although she had previously identified it as the “Captain Garrison House” or the “Old Post Road Tavern” in a 1935 article on the history of Sparta. It is little wonder that descendants of the Geisler family, who rebuilt on the property after the Garrison house was demolished in 1884, were reportedly offended by the name.[5]

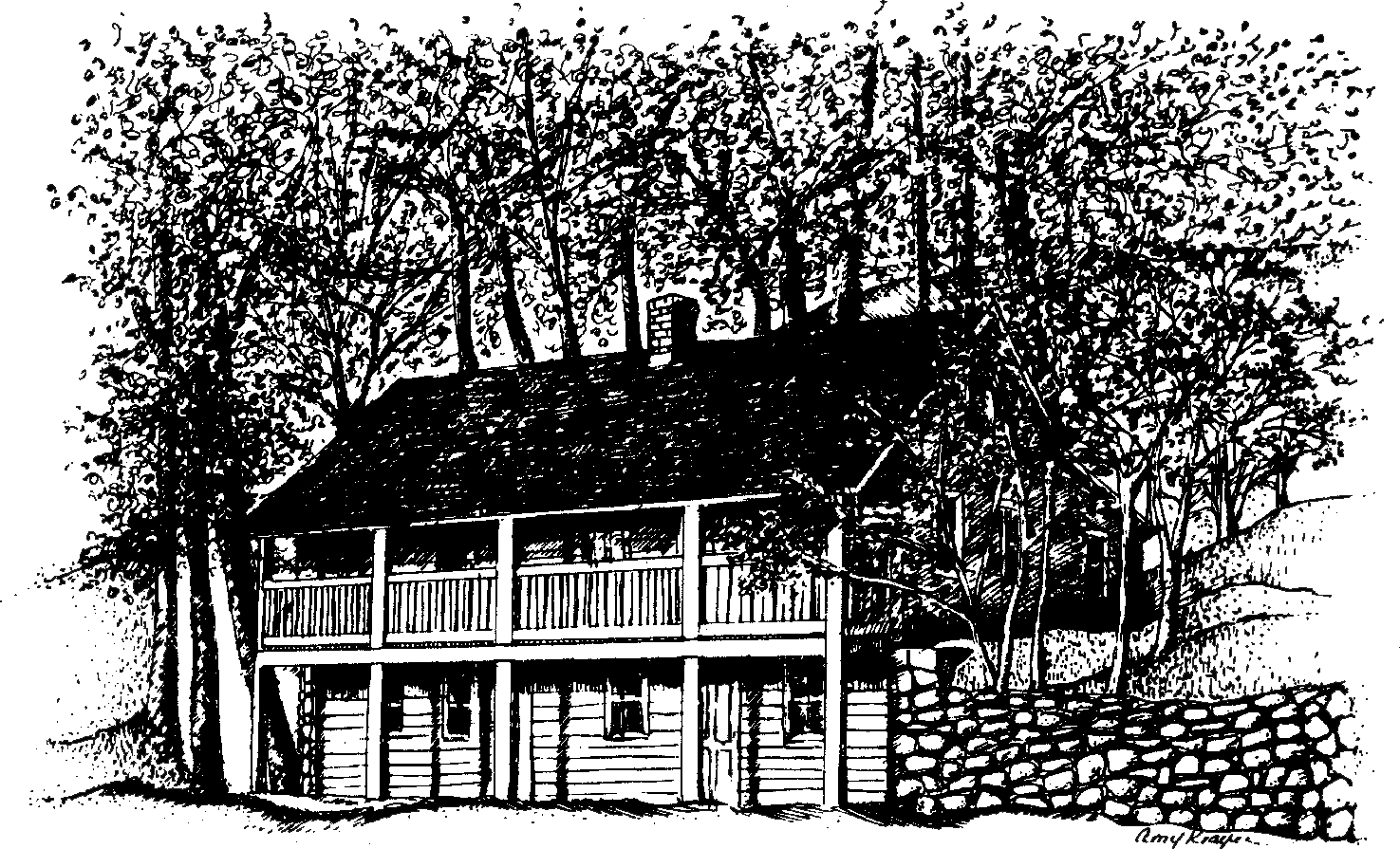

The building most people now know only as the “Jug Tavern,” more formally the “Davids-Garrison/Jug Tavern,” is today between one hundred fifteen and one hundred twenty years old.[6] Although the building is not the colonial relic it was once believed to be, there is still a long history of life at the site, with development beginning in the first quarter of the eighteenth century and settlement there by its end. Moreover, there is reason to believe that the present building is very close in design to the early house it replaced. A painting of the property by a local girl, Ludmilla Pilat, thought to date to 1883, just before the Garrison house was demolished, depicts a building with apparently gaping eaves and exposed rafters—the “rack and ruin” described in the 1884 newspaper story. Although the painting is roughly executed, the long, two-story building, with a lower porch, and a door in the second story where an upper porch may have been, looks very much as the Jug does today. But for the two chimneys at each end of the house, now a single one moved to the center, it would appear that the Geisler family who owned the building at the time of its demolition rebuilt it based on what it had been.

Early History of the Site

Before 1785, the land on which the Jug Tavern now stands lay within the bounds of the enormous estate of the Philipse family, a property which extended from Spuytin Duyvil to the Croton River, and was designated the “Mannour of Philipsborough” by the British crown in 1685. With the local native tribes who had been there for millennia, tenant farmers lived on these lands, holding leases for large tracts of the Manor. Only the scantiest records and no maps survive to suggest where these tenants’ lands lay, but the careful analysis of roadmasters’ assignments have led historians to determine that in the early half of the eighteenth century land incorporating the present Jug property was leased to one Charles Davis/Davids.[7] After 1744, tenancy records for this land are inconclusive. Several of Charles Davids’s sons (William, John, Harmand, and David) are shown as tenants of Frederick Philipse in a handful of surviving rent rolls for the 1760s and 1770s, but there is no information to show where the tracts they leased were located.[8] Members of the Davids family almost certainly retained the leasehold, however; in 1785, Philipse tenants who had supported the American cause during the Revolution became eligible to buy their land because their landlord, Frederick Philipse, had forfeited his right to the properties by remaining loyal to the British crown. That year Peter Davids, another son of Charles Davids, purchased for the extraordinary sum of £600 a two hundred-acre tract of land incorporating present-day Sparta including the Jug Tavern property.

By this time, the area in which the Jug Tavern lies had already been somewhat developed. The beginnings of development at the site were probably about 1723, when the route was laid for an inland public highway that would eventually link New York City with Albany as the Albany Post Road. Located at a juncture where the new “King road”[9] passed over a stream flowing down to a small inlet on the Hudson River, the Jug Tavern land overlooked a natural crossroads. By 1744—and probably earlier—a bridge crossed the brook there.[10] By the 1780s, a road led from the Post Road to the Hudson River just south of the brook, and in the later 1790s, the community of Sparta was established along its north side with its own road leading down to the river.

John Hills’s 1785 map of the Philipsburg Manor lands for the Commissioners of Forfeitures is usually identified as first document to show a building at the Jug site, however the mark appears at quite some distance north of the point where the Post Road crossed the brook at present-day Sparta. Similarly, Christopher Colles 1789 survey of the roads of America shows a small structure marked Davis that is closer, though still at some distance from the place where the brook is indicated. The first map to illustrate a building on what can be confidently identified as the Jug Tavern site is J. Harmer’s 1795 survey map of the developing community of Sparta.

Although Harmer’s map is undoubtedly partly a proposal—the grid-like street pattern did not develop as it is shown because of the rocky ridge in the area—the long rectangular building on the north side of Sparta Brook where the Post Road crosses it appears to illustrate an existing structure. It is, after all, one of only a handful of buildings indicated on a plan that lays out dozens of lots, and it is situated at an angle, in line with the Post Road, rather than confirming to the strict grid established for the rest of the community.

Harmer’s map shows that by November 1795, when it was drawn, the land on which the Jug Tavern is situated, along with all the land that constitutes present-day Sparta, was apparently no longer in the hands of the Davids family.[11] Following Peter Davids’s death, parts of his property were sold by his heirs and parts may have been forfeited to cover his debts. J. Harmer’s map shows that in late 1795, the “Widow Davis” still owned land to the north of Sparta, but not apparently the Jug property. Did she continue to live on the property, as Philip Field Horne believed,[12] or was the Davids house not on the site of the “Old Garrison House”/Jug Tavern, but further up the road?

Too many questions remain to be able to answer this question satisfactorily, and there is evidence both in support of and contrary to both positions, all of it difficult to interpret. In addition to the doubts already raised, no deeds survive to document the parties who transferred ownership of the Jug property to the Garrisons, who owned it by 1814. On the other hand, lists of road- or pathmasters and their districts for 1795 and 1810 describe “the bridge by Davids” and “the turnpike Bridge by the Widow Davids.”[13] Frustratingly unclear is whether the bridge is by the Davids’s house or by their land, and how near by. As an established family in the area, the Davids house and/or property could simply have been the best-known landmarks in the vicinity, not the closest, for local officials and roadmasters to use when delineating road districts.

Garrison Ownership

Most of the nineteenth-century history of ownership for the parcel of land on which the Jug Tavern now stands is incomplete in the public record.[14] The paper trail of deeds going back from 1976, when Geisler descendant Elenor Mowatt and her husband William transferred ownership of the property to the Town of Ossining, is complete going back only as far as 1882. Fortunately, the existing documents refer to earlier deeds now lost, leaving a partial history of the property’s owners in the early nineteenth century.

The present parcel of land, or a somewhat larger tract, was probably created after the David ownership ended, perhaps about 1795 when J. Harmer drew his survey of Sparta, which is the first document to indicate lots in the area (it is not known if the divisions were speculative or not). As noted, no record survives of the transfer of the Jug property from the Davids, or intermediaries,[15] but at some point before 1814 one Nathaniel Garrison and his wife “Annas” (usually spelled Annis) acquired title to the land. That year, according to much later deeds, Nathaniel and Annis conveyed ownership of the property to Tallman and Samuel Garrison, who may have been Nathaniel’s brothers.[16] Three years later, the will of Tallman Garrison conveyed his undivided half of the same property, jointly owned with his brother Samuel, to their brother William Garrison.[17] Tallman’s will describes “a frame house” on the premises, and map of Sparta made three years after shows a building in two sections, one smaller, situated in front of the rocky bluff near the point where the road from Sparta meets the Old Post Road.[18]

It is not known why or how Nathaniel and Annis gave up their title to the property, but they apparently continued to live there. Local lore in the early twentieth century told of “Aunty” Garrison selling thread, needles, home cures, candy, and even yard goods at the house,[19] and an 1862 map of Sparta depicts a building on the site marked “Mrs. Garrison.”[20] The Garrisons may have eventually regained the right to property, because Annis “Garretson” paid property taxes between 1860 and 1869,[21] and because it was the sons of Nathaniel and Annis’s daughter Jane Groves who sold the property, with another parcel of land, to Michael Geisler in the 1880s.[22] If an elderly Annis Garrison was selling goods from her house in the 1860s, it was a small operation, since the Assessment Rolls indicate taxes only for a house and property, not for a shop, as other entries in the same books do. Ten years earlier, in the 1850 Federal Census, Annis Garrison was listed without an occupation, although the family—which included her son Nathaniel, daughter Peggy (Margaret), and an unknown relative, John Garrison—does seem to have taken in boarders.[23]

The elder Nathaniel Garrison had died in 1843, aged about seventy-six. His poor health—he walked with to canes—may have prevented him from working later in life. In 1792, a man with his name served one year as a road- or pathmaster for a length of the Post Road adjacent to the Peter Davids property,[24] but by 1837 Garrison told a judge in a probate hearing that he did “little or nothing, sir.” When asked, “what business do you follow when you are able to do business?” he answered that he had done some farming at times and had driven a stagecoach at others.[25] Popular stories about a tavern on the property are usually associated with Nathaniel Garrison, and claim that liquor was sold there during the Revolution.[26] These accounts contradict the available evidence, since Garrison is not known to have lived on the property until much later . Previous research, notably that of William Shopsin and Mosette Broderick, have ruled out the existence of a tavern there in the eighteenth-century based on the fact that Peter Davids was never granted a license to sell liquor. It is worth noting, however, that some of the tavern anecdotes imply that the sale of liquor “by the jug . . . not by the glass” was illegal, and would therefore have gone on without a license. While there are contradictory elements about the traditional stories, they seem to have been ubiquitous in the early twentieth century and may have their origin in a long-ago, poorly remembered truth. While there is no evidence to suggest that the Garrison’s house was once known as the Jug Tavern, there is not enough evidence to rule out the sale of liquor there.

Geisler Ownership

In early September 1884, when the Democratic Register described the demolition of the “Old Garrison House,” the sale of the property to Michael Geisler had only weeks before been finalized.[27] Notably, the week before demolition was reported, a short notice had appeared in the same paper that the Sparta home of Michael Geisler had burned to the ground.[28] Recently, this has been interpreted to mean that the Garrison house had caught fire, and that its burned remains were demolished the following week. There is reason, however, to believe that this may not be the case. Deeds show that Michael Geisler owned more than one property in the area. Moreover, the newspaper account of the demolition makes no mention of a fire, and indeed states that while “the edifice has been left to rack and ruin for some years past, some of the timbers are quite sound, and the old-fashioned split lath are in prime condition.” In the late 1970s, architecture specialists William Shopsin and Mosette Broderick closely inspected the fabric of the building, including some of its hidden structures. According to John P. R. Lee, who has had a long association with the Jug Tavern and remembers Shopsin’s work there, no evidence of fire was found (although at this date the inspectors did not know of the Democratic Registernotice, and would not perhaps have been looking for fire damage).

It is possible that, in the week after the destruction of his home elsewhere in Sparta, Michael Geisler began the work of building a new home on the property he had just acquired, knocking down the decaying Garrison house that stood there in “rack and ruin.” Since Shopsin and Broderick’s inspection found a mixture of structural elements, some of them typical of early construction, in a building now known to have been built at the end of the nineteenth century,[29] it seems possible that the Geislers not only rebuilt in the style of the Garrison house, they may have incorporated sound materials or parts from the older home. This may help to explain why, in the early twentieth century, so many people in Sparta looked upon the Geisler house as a relic from the early history of their town.

“George Washington Slept Here”

While some of the stories that have convoluted the known history of the “Jug Tavern” were certainly the result of flawed memories and imperfect retellings, others were the kind of wishful anecdotes that were so typical of the period in which they emerged. From the late nineteenth century, and especially in the early twentieth century, patriotic and nationalistic impulses led journalists and local historians, professional and amateur, throughout the American northeast and mid-Atlantic to add both glamour and gravitas to local sites by emphasizing associations, documented or otherwise, with the most celebrated colonial and especially Revolutionary and Federal-era figures and events. Founded on kernels of truth or not, “Jug Tavern” stories that featured General Washington stopping at the property, even staying there some insisted, as well as links drawn to more illustrious Garrisons, such as Captain Reuben and Marvel Garrison, were all inspired by this way of seeing and appreciating history.

Frank and Narcissa Vanderlip’s project to rebuild Sparta, underway in the 1910s and 20s, is an interesting corollary to these kinds of stories about the Jug and other Sparta landmarks, and may partly have inspired the interest in local history that spawned them. In an effort to revitalize the community, which had fallen into decline, the Vanderlips bought up house after house in the village and, with the assistance of a firm of New York City architects skilled in historical revivalist design, refurbished them to emphasize the colonial and Federal roots of the community, removing later nineteenth-century additions to many, and making major changes to others. The Federal-era architecture of the house at 2 Liberty Street, for instance, was enhanced with an addition in the form of a classical porch facing the Hudson River and an elegant early nineteenth-century iron railing salvaged by the Vanderlips from a property in New York City.[30] And at 12 Liberty Street, the architects completely altered the narrow brick house once on the property, with an addition that follows the curve of the road to create Georgian-style symmetry and proportion in the southern colonial-inspired building, complete with mullioned fanlight, broad brick chimney, and circular window. It is an interesting parallel that, as the Jug Tavern’s history was being told to emphasize colonial and Revolutionary roots, the Vanderlips were recasting the town in an idealized image of a Federal-era village. As such, the history of Sparta is a fascinating case study of what is now called the Colonial Revival in America.

Today, we have the advantage of perspective over Sparta’s early historians, the distance of time and culture that allows us to see that the history they told reveals as much about them as it does about the past; to see the image of their times in the version of the past they embraced. We also have the advantage of learning from their choices, and seeing the foibles in them. With so much of the concrete history of Jug Tavern property still in doubt, perhaps never to be known, and so much, if not all of the early building lost, any interpretation of it to a period earlier than the twentieth century—unless done with great skill—risks repeating fantasies of the past, and seeing the history one wants to see, rather than what is tangible.

Repositories visited:

NYPL – updated Davids family genealogies and various

Westchester County Archives, Land Records – title search

Ossining Historical Society – tax assessment records, Martha Mowatt file with original deeds, Sparta files

Historic Hudson Valley Library, formerly Sleepy Hollow Restorations: houses copies of all materials in their archives, in the library at the Rockefeller Library in Pocantico Hills, and elsewhere, including foreign records such as the Philipse family papers, now in Wales

Notes:

[1] See for instance, “Vanderlip Wakens Sparta from Sleep of Centuries,” Democratic Register, 4 December 1920, reprinted from the Sunday World, 28 November 1920; “Old House at Sparta is a Revolutionary Relic,” Daily Reporter (White Plains), 5 August 1935; and “Garrison House in Sparta Once Washington’s Quarters,” and “Washington Once Drank from Sparta Inn’s Well,” both from the same unidentified Westchester newspaper, 31 July 1935 and 27 February 1936; Ossining Historical Society (OHS), Jug Tavern Files: “Newspaper Clippings 1935-.”

[2] Unidentified Ossining newspaper, 24 February 1975; OHS, Jug Tavern Files: “Newspaper Clippings 1935-.”

[3] The tavern story probably comes from Adelia Foster, a schoolteacher, who wrote down reminiscences and the local lore of Sparta in and unpublished manuscript in 1916, location unknown. According to her daughter, Almira L. Acker, Mrs. Foster eagerly shared stories of early Sparta with her children, and Mrs. Acker recalled what she had learned from her in a conversation with Louis Engel in 1978; [Louis Engel], “Notes on Conversation with Mrs. Acker,” unpublished manuscript, 14 July 1978, copy at the OHS in a Sparta File “ Deeds/History.” Mrs. Foster’s older daughter, Helena May Foster, became an avid local historian and also shared her mother’s stories, both in unpublished reminiscences and in an article for the Westchester County Historical Society; see Helena May Foster, “Sketch of Old Sparta,” manuscript version, Jug Tavern of Sparta (JTS) files; Foster, “Sketch of Old Sparta,” Quarterly Bulletin of the Westchester County Historical Society 2, no. 1 (January 1935): 1-6; interview with Helena May Foster by Dr. V. Redway, unpublished manuscript, 23 February 1947, Jug Tavern of Sparta (JTS) files.

[4] Frank A. Vanderlip, Jr. to Marion Cormier and Greta Cornell, 25 October 1976, OHS, Sparta File “Updates 1700s-1800s, 1940.” A photograph, thought to date from 1895, shows the grapevine on the porches that Vanderlip described; William Shopsin and Mosette Glaser Broderick, “The Davids-Garrison--‘Jug Tavern’: An Historic Structures Report,” unpublished report, January 1978; rev. 1979, fig. 1.

[5] According to William Shopsin and Mosette Broderick, Elenor White Mowatt, the last private owner of the Jug Tavern, remembered her mother, Elenor Geisler White, and an aunt being “enraged when they heard their house referred to as ‘Jug Tavern’”; Shopsin and Broderick, endnote 1. While Shopsin and Broderick’s interpretation of the documents associated with the Jug property is flawed, and their history of its ownership contains several errors and some unfounded assumptions, William Shopsin knew Elenor Mowatt, and undoubtedly had heard this story from her.

[6] A photograph, believed to date from about 1890, shows the house much as it appears today, with two tiers of columned porches and a center chimney; Shopsin and Broderick, fig. 1A.

[7] See especially, Philip Field Horne, “Inquiry into the History of ‘The Jug Tavern,’ Sparta, New York,” unpublished manuscript, 26 March 1975, OHS, Jug Tavern File: “Newspaper Clippings 1935-”; and Horne, A Land of Peace: The Early History of Sparta, A Landing Town on the Hudson(Ossining, NY: Ossining Restoration Committee, Inc., 1976). Charles is known as “Carel” in the records of the church he attended, now the Old Dutch Church at Sleepy Hollow. The church’s Protestant Dutch clergy recorded largely Dutch forms of the names of members of the congregation--who were also largely Dutch--in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Charles, however, may have been known by the French pronunciation of his first name (he immigrated to New York from French Canada), since his name appears frequently in the church records as “Sarel,” “Siaarel,” “Zarel,” or “Zharel,” which could all be interpreted as phonetic spellings of the French “Charles.” His last name appears as “Davids,” “Davidse”,” Davidze,” “Davidssen,” and other similar variations; records reprinted in David Cole, First Record Book of the "Old Dutch Church of Sleepy Hollow” (Yonkers, NY: Yonkers Historical and Library Association, 1901). Recent research updates the Davids family history and genealogy known to Field Horne, suggesting that Charles had a French father and a Dutch mother; see James L. Hansen, “The Origins of the Montross and David Families of Tarrytown,” New York Genealogical and Biographical Record 122, no. 4 (October 1991): 193-201; and 123, no. 1 (January 1992): 30-34.

[8] “List of Tenants With there Respective Rents as they are Now Raized [sic],” January 10, 1760, copy, Historic Hudson Valley Library (HHV), PA 820; “A List of the Tenants that have paid their rents to me at New York Due the 22d Decem. 1777,” copy, HHV, PA 823; “Rec of Rents Rec’d Decem. 1777,” copy, HHV, PA 817; “A List of Tenants that have paid their Rents to me at New York due the 22d December 1778,” copy, HHV, PA 822; “Rent Received for the Year 1779,” “Rent Rec. 1779-80,” and “Rent Received for the year 1781,” copy, HHV Library, PA 809. Field Horne suggests that John held his father’s farm; Horne, Land of Peace, 9.

[9]Term used in the Philipsburg Clerk’s record book, 1741-1778; original at the New York Genealogical and Biographical Society; transcribed in “The Town Book of the Manor of Philipsburg,” The New York Genealogical and Biographical Society Record 59, no. 3 (July 1928): 203-213.

[10] That a bridge crossed the stream at this point in 1744 is, in addition to being a reasonable assumption, concluded from an entry that year in the Philipsburg Clerk’s record book that Abraham Aerse was to oversee the “King rood” (post road) “from the upper mills to Charl Davids bregs” and that Johannis Van Tesxel would do so “from said brgh to Crotens River”; ibid., 204. Since Charles Davids is thought to have leased this land in that period, the conclusion is that the bridge referred to crossed the stream by the Jug Tavern.

[11] In November 1795, this land must have been held by the executors of the estate of James Drowley, who after 1794 held a mortgage for part of Peter Davids’s land. Davids and his wife had mortgaged seventy acres in 1789, apparently to cover debts generated as early as 1772; Horne, Land of Peace, 19-20.

[12] Horne, “Inquiry,” [5].

[13] Carsten Johnson, “The Minute Book of the Town of Mount Pleasant, County of Westchester, State of New York, 1788-1836: A Transcription of pages 1 to 151 and the road master lists appended to the original copy which is in the keeping of the Clerk of the Town of Mount Pleasant, 1 Town Hall, Valhalla, New York,” unpublished manuscript, Tarrytown, NY, 1978, 39, 120-21; copy in the Historic Hudson Valley Library.

[14] Since deeds are contracts between two parties, the originals of these documents remain with the parties involved. Most deeds, especially more recent ones are copied for the public record, including Westchester County deeds, copies of which are retained by the Westchester County Archives in White Plains, New York. Therefore, while deeds may have been executed for past property exchanges, if they were not publicly recorded they are lost to the record unless the originals can be found.

[15] See note 11 above. Most of the deeds for land sold by the executors of James Drowley’s estate were never recorded.

[16]Westchester County Deeds (WCD), 24 December 1882, Liber 1019:228; WCD, 30 June 1884, Liber 1050:191. The relationship of Nathaniel and Annis to Tallman and Samuel Garrison remains unclear. Tallman Garrison’s 1819 will shows that his father, still living, was also named Nathaniel Garrison. This is not likely the Nathaniel Garrison, married to Annis, who transferred ownership of the Jug property to Tallman and his brother Samuel. Nathaniel and Annis are thought to have had three children: Nathaniel, Margaret (Peggy), and Jane, whose names do appear in various records, including the 1850 Federal Census. Tallman’s will, however, does not mention a brother named Nathaniel, only brothers William and Samuel; Westchester County Wills, Liber J:163, proved 20 September 1819. Readers should know that Grenville C. Mackenzie’s “Families of the Colonial Town of Philipsburg” entry for the Garrison family lists Tallman, Samuel, Nathaniel, and William as sons of Richard Garrison.

[17] The language of the will may suggest that Tallman and Samuel owned an undivided half of half of the property: “Half last [the property] belongs to my brother Samuel Garrison and myself, each with undivided half of land”; quoted from a handwritten transcription in the Jug files; public record should be checked for its accuracy and meaning.

[18] The present location of this map is unknown to the writer; it is reproduced in Horne, A Land of Peace, 22.

[19] This story seems to originate with Adelia Foster, and circulated by her daughter Helena. Adelia or Helena may have heard “Aunty” for “Annetje” or “Annetie,” a common name and frequent transliteration of names like Ann, or Annis, in Dutch-dominated Westchester County. Adelia Foster’s younger daughter, Almira Acker, in an interview with Louis Engel in 1978, contributed the second-hand memory about the yard goods.

[20]Map entitled “Village of Sparta,” 1862.

[21] Assessment Rolls for the Town of Ossining, 1860-1869, OHS. Annis Garrison probably paid taxes earlier than this, but the Ossining Historical Society owns only those volumes from 1860. During this period the assessed value of Annis Garrison’s property—listed first as a house and a lot and later as a house and two lots—declined from $200 to $175. Her name disappears from the tax rolls after 1869, when she is said to have died.

[22] WCD, 24 December 1882, George Groves and Ida L. Groves, his wife, to Michael Geisler, Liber 1019:228 [the Jug property]; WCD, 30 June 1884, James Groves to Michael Geisler, Liber 1050:191 [the Jug property]; WCD, 8 August 1884, George Groves, Ida Groves, his wife, and James Groves, to Michael Geisler and Mary Geisler, his wife, Liber 1050:87 [a property west of the Jug property, also once owned Nathaniel and Annis Garrison and conveyed to Tallman and Samuel Garrison in 1814].

[23] Philemon Yeomans, a farmer with a wife and small son, is shown living with the Garrisons; he is actually listed as the head of the family; Federal Census for 1850, Westchester County.

[24] “Minute Book of the Town of Mount Pleasant,” 27.!

[25] Probate contest, 1837; noted in “Garrison House in Sparta Once Washington’s Quarters,” unidentified Westchester newspaper, 31 July 1935, OHS, Jug Tavern File: “Newspaper Clippings 1935-” file. The article cites the research of Elliot B. Hunt of Ossining as its source.

[26] Some twentieth-century accounts recall that it was the Garrison’s relative, Reuben Garrison, who was the liquor purveyor; see “Garrison House in Sparta Once Washington’s Quarters”; and “Old House at Sparta is a Revolutionary Relic,” Daily Reporter (White Plains), 5 August 1935.

[27] On 24 December 1882 George Groves and Ida L. Groves, his wife, conveyed their interest in the Jug property to Michael Geisler; one and a half years later, on 30 June 1884, James Groves conveyed his interest in the Jug property to Michael Geisler; Westchester County Deeds (WCD), 24 December 1882, Liber 1019:228; WCD, 30 June 1884, Liber 1050:191.

[28] “Fire,” Democratic Register, 30 August 1884; Greta Cornell also discovered this notice.

[29] “Analysis of Original Fabric and Subsequent Alteration,” in Shopsin and Broderick, n. p.

[30] Frank Vanderlip Jr. wrote to the Ossining Restoration Committee about how his father obtained this fence; Frank A. Vanderlip, Jr., to Marion Cormier and Greta Cornell, 25 October 1976, Sparta File “Updates 1700s-1800s, 1940,” OHS.