The History of The Jug Tavern

(Davids-Garrison House)

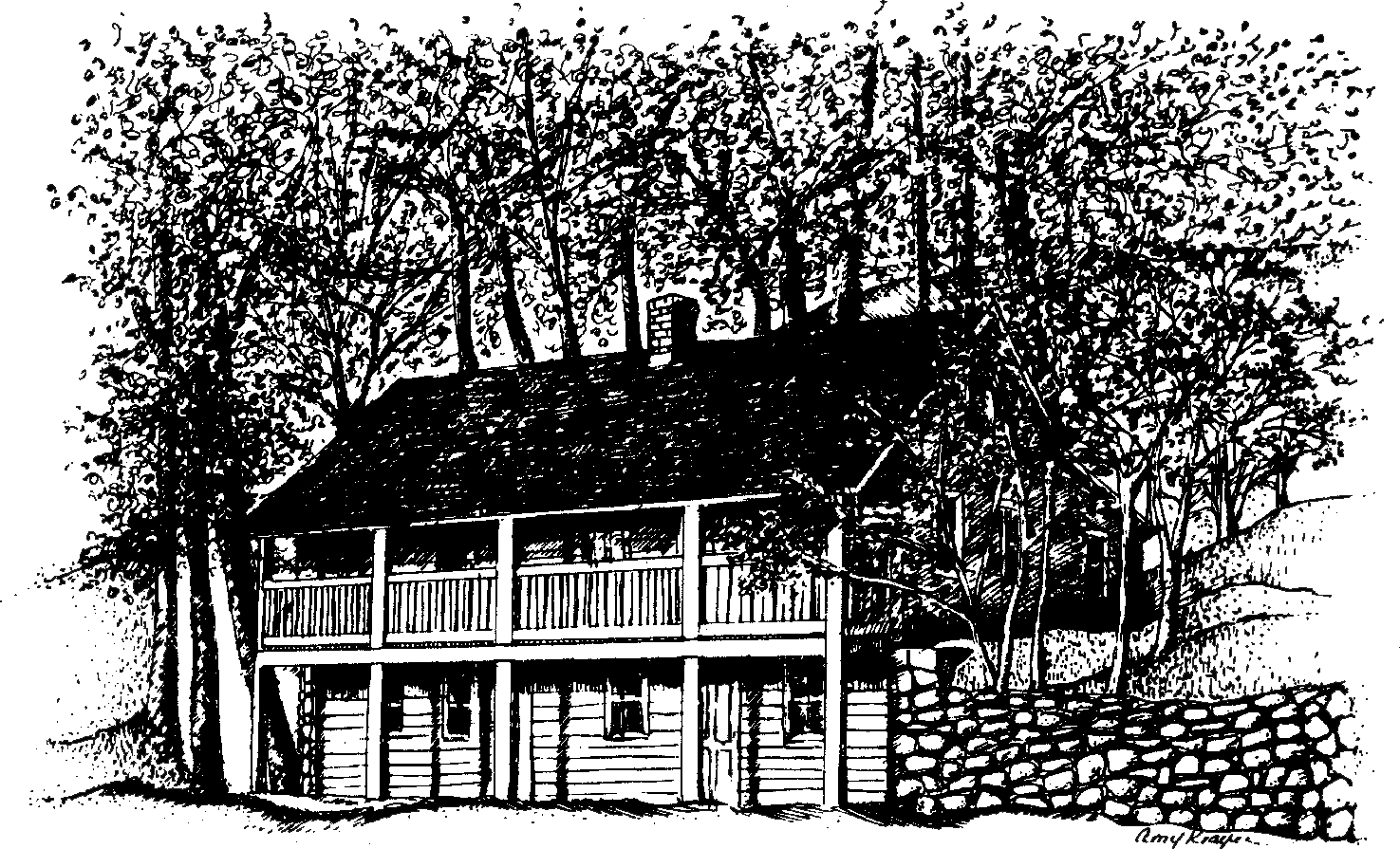

The Jug Tavern (1883) by Ludmilla Pilat Welch (1867-1925) before structure rebuilt by Geisler family. Note two chimneys and bridge over Sparta Brook.

They say that George Washington watered his horse at The Jug Tavern as his troops passed by, and that The Jug Tavern was so named due to illicit liquor sales. The real story of The Jug Tavern is that for over 200 years, it has stood at the gateway of Sparta, Ossining’s earliest neighborhood and historic district since 1974. Today the building serves as a symbol of community engagement and activism. It is a preservation success story. Saved from demise during the national bicentennial, The Jug Tavern is a testament to the efforts of many people: Ossining residents, government officials, local community groups, and many volunteers. A treasured Ossining landmark, it has been on the National Register since 1976.

The Jug Tavern (known by this name only since the 1940s) predates the settlement of Sparta, and was built as early as 1780s by Peter Davids, a tenant farmer for Philipsburg Manor. From 1814 Nathaniel and Annis Garrison called it home, and eventually doubled the size of the building. Annis (known as Auntie Garrison) outlived her husband by 26 years and died in 1869 at the age of 99. Local lore says that she sold candy and sewing notions out of the house. Nathaniel and Annis are buried in Sparta Cemetery. Into the 20th century the house was referred to as the “Old Garrison House.”

The Jug Tavern (1950s) with covered well, which was buried sometime before 1974.

Sparta resident Michael Geisler, a Prussian immigrant and cooper by trade, purchased the property in 1882 from a Garrison descendant. Two years later the building was demolished for reasons unknown and rebuilt in the same style on the original foundation. The central chimney was put in at this time. The house remained in the family for 94 years, occupied by Michael Geisler Jr. until his death in 1950. The property was sold by William and Elenor Mowatt (Michael Jr.’s niece) to the Town of Ossining in 1976 for $15,000. It had been vacant for some time before the sale.

Reports that this building served as a tavern have not been confirmed by research or archaeological evidence. For about 200 years, this building was simply a home. By the 20th century, the ground floor contained two rooms: a kitchen and dining room, balanced by a bathroom on the south end and a staircase on the north end. A living room and three bedrooms occupied the second floor.

Sitting in this building today is no small thing. In 1974, the future of The Jug Tavern was uncertain. At this time, the Town of Ossining was approached to purchase and restore the building for use as a center for local national bicentennial celebrations. Members of the Sparta Association (a resident group since the 1950s) raised awareness of the historic significance of The Jug Tavern and gathered signatures in support of its preservation. Eventually the Town purchased the property in 1976, and the Ossining Restoration Committee (formed in 1975 by Louis Engel Jr.) was tasked with fundraising and carrying out the restoration. The future of The Jug Tavern looked bright.

Jug Tavern notecard (1976) illustrated by Karen Pellaton for Ossining Restoration Committee.

In 1976 the outside of The Jug Tavern was restored to its 1890 appearance with a new coat of red paint and a repaired roof. The bicentennial passed and funding dwindled—a full restoration would wait another 15 years. In 1986, the property eventually was purchased by the newly formed Jug Tavern of Sparta whose sole purpose is to preserve and maintain the building for future generations. The group completed renovations in 1991. The first floor became a meeting room with a small kitchenette and restroom. A new one-bedroom apartment with a private entrance was built on the second floor. The exterior of the building was repaired and painted gray.

The Jug Tavern of Sparta today.

In a 1986 letter to Florence Brennemann, first president of The Jug Tavern of Sparta, vice president John Lee writes, “The Davids were merely one of the Philipse’s many tenant farming families. That their house should survive today, is pure luck.” The Jug Tavern of Sparta continues that luck today through community support and many volunteers. Since 2015, The Jug Tavern has upwards of 300 visitors per year, who take walking tours, attend programs, and keep history alive.

—By Martha Mesiti