The [Ossining] Democratic Register, Saturday, December 4, 1920

Vanderlip Wakens Sparta from Centuries of Sleep

Buying Homes for Teachers in School He Established,

Financier Extends Scope of Original Plan and Will Make

Quaint Historic Village a Model Dwelling Place

[Reprinted from the New York Sunday World, Nov. 28, 1920]

Frank A. Vanderlip, once a poor boy and afterward president of the National City Bank [now called Citibank], has solved the housing problem for the teachers in his community school at Scarborough-on-Hudson by buying a little, old pre-Revolutionary hamlet called Sparta, half a mile below Ossining, states a gifted writer (gifted with romance and great imagination) in last Sunday’s New York World. He aims to make it into a beautiful village. Sparta, basking for two centuries on the sloping eastern shore, has been the typical sleepy Hudson river hamlet for all those years. The building of a house was a great event. Changing ownership of a tiny cottage and garden recalled to the old residents the "great land transaction" after the revolution.

All of the land of the rich Philipseburg Manor, stretching from VanCortlandt Park in New York to Croton and owned by Frederick Philipse, lord of the manor, was confiscated by the Government because of the British sympathies of the Philipse family and sold to the tenants who had been true to the American cause. Sparta is a village where for years the chief social event was the weekly prayer meeting conducted by Elder Holden and the preparations for the Christmas celebration, when Mr. Holden himself played Santa Claus for the children.

It was a hamlet of 15 or 20 ancient houses nesting among gnarled apple trees and rose-covered garden fences along a meandering country road leading down a ravine between Murray Mountain and the Sing Sing kil, where was the lime quarry that furnished employment to some of the dwellers. Down by the river, with its broad sweep of blue waters out of Haverstraw Bay and around the massive base of old Hook Mountain and the Reaping Hook into the Tappan Zee to the south, were old lime kilns where the sugary looking marble cut out of the quarry was burned to plaster to help build Manhattan into a great city. It was a quiet, peaceful spot, was old Sparta, the home nest of such families as the Storms, Lyons, Trathens, Birds, Loughlins, Robinsons and Sherwoods.

Then the cement business partly knocked out the lime business. The dock on the river front fell into disuse. Some of the old families moved away. The young folks sought employment elsewhere, and Italian and Swedish gardeners and laborers on the neighboring rich estates took their places in the life of the village. Historic old houses that had figured in the lives of Gen. Washington, Gen. Israel Putnam, Major Andre and others of the Revolution began to have a tired and sometimes gray and neglected look. Roses ran wild over the back yard fences into the blackberries and burdocks. The peppermint and catnip, once confined with precision to grandma’s garden beds, strayed out along the dusty road. The sleepy village went to sleep.

Then came the great war [World War I]—and Sparta sent its valiant little handful of patriots, as it had done in the Revolution, the Civil War and the Spanish War—and the housing problem smote the whole country. A little south toward the mystic Sleepy Hollow of Washington Irving, is the country home of Frank A. Vanderlip, with ideas about community neighborliness and friendship. The teachers in Mr. Vanderlip’s private school needed homes to live in. He already owned some land in the village of Sparta, and he bought more, including some of the historic old houses, with the idea of making them into homes for his teachers and any other country-loving folk who might want to live in a revivified hamlet such as he proposed to make Sparta.

Purchasing a part of Sparta, enough to change its complexion, really grew in Mr. Vanderlip’s mind as part of his community betterment schemes. Some years ago Mr. Vanderlip discovered, a friend said yesterday, that he had five or six healthy minded children of his own to educate, and set out to find the best way to do it. He employed [the best?] educators to decide what was [the best?] system of education.

After mature consideration they all came back with a report that the public school system, or something closely following it, was the best for Americans who intended to live in America. But there was no public school close by, and Ossining was a long way off for little legs to trudge. So Mr. Vanderlip opened a public school of his own in a building on his estate, inviting the neighboring families to send their little folk there. The school prospered and grew, and Mr. Vanderlip called a neighborhood meeting of parents and offered to build a large modern school building if the community liked the idea—and it did. There are now 250 pupils, somewhere around 20 teachers, and it is an up-to-date modern school, with the best of the public and private school innovations. [The building is now the Clearview School, on Route 9 in Briarcliff Manor.]

The community movement did not stop there. Mr. Vanderlip added a fine modern theatre to the school building, and the neighborhood organized a company of players which gives plays, sometimes exchanging with similar organizations at White Plains and elsewhere. Forums are held where national subjects are discussed, there is a musical circle with regular assemblies, and the whole neighborhood feels itself part of this community work. Because he owned part of the little village of Sparta and wanted to help it, Mr. Vanderlip encouraged the opening of a community house with a reading room in one of the old houses there and will add a library and other conveniences, it is said.

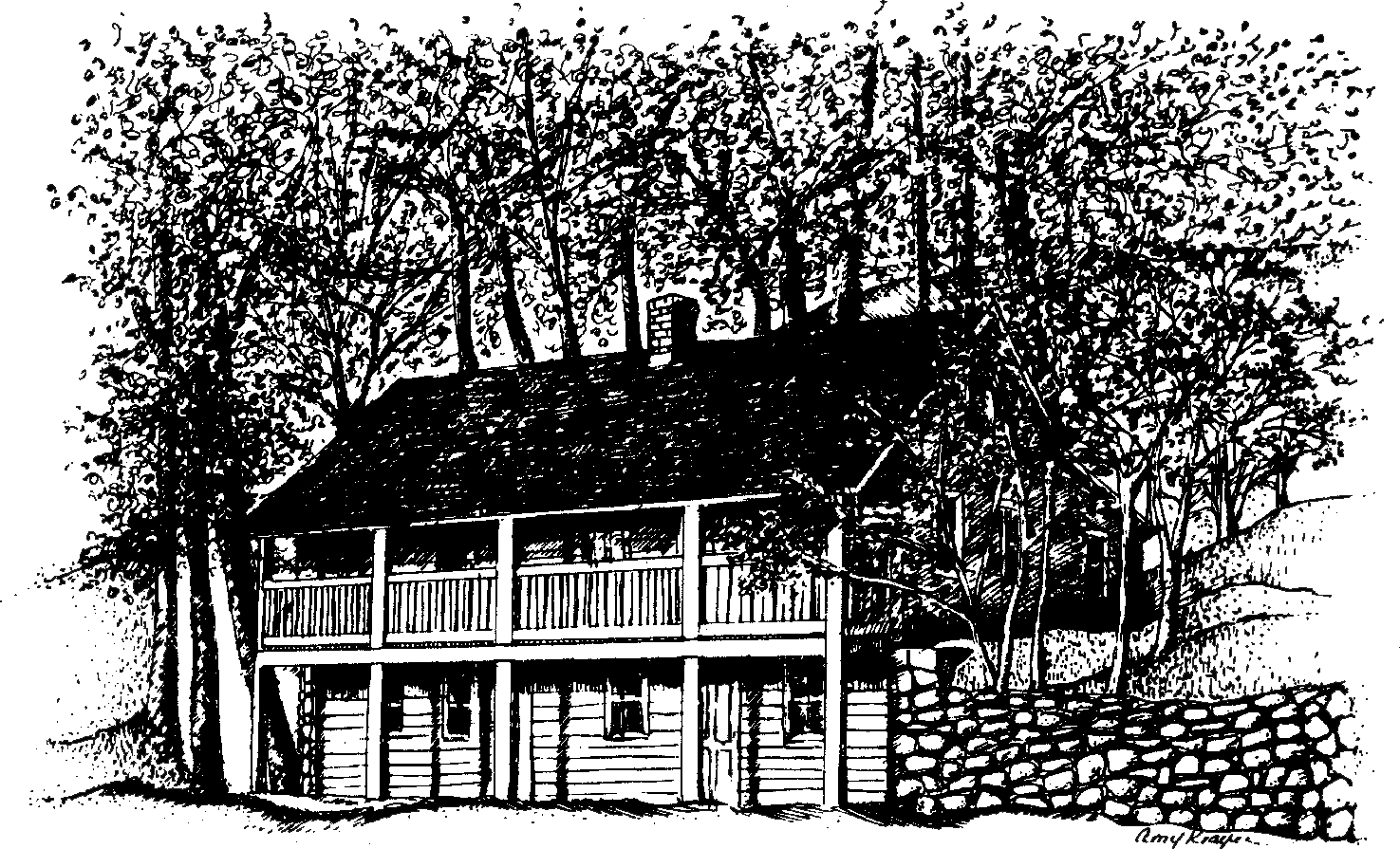

To furnish houses for his teachers he first built several out on Revolutionary Road, running past Sparta to the east. This road is the old Albany Post Road, and just beyond the cemetery and the hothouses of Pierson, the florist, the Village of Sparta begins where Rockledge avenue turns down toward the river at the old Garrison and Miles See’s house, both Revolutionary family names. This quaint old wooden house, basking beside the road, is said to have been used as a headquarters by Continental Generals during the Revolution, and the ancient stoned-up well in the yard where the Albany stagecoaches used to stop for water, is said to have given a drink to Major Andre on his memorable trip from West Point down to Tarrytown, where he was captured. It is called the Andre well. In the cellar of the old house British prisoners were sometimes held.

The houses Mr. Vanderlip built on the Revolutionary Road were not enough for the teachers and so he bought more in Sparta, though he does not own half the village, and is remodeling them. The effect on the sleeping village was instantaneous. It awoke with a start. It put up the price of real estate. Mr. Vanderlip has houses enough to change the appearance of the place from Rip Van Winkle’s village to Spotless Town, and announces he does not care to buy any more unless somebody wants to sell at reasonable prices.

He has not bought the village saloon, for instance, though he owns half the building and will renovate that as far as the party wall. Nick Sallazzo, whose liquor license still hangs in the window, has not indicated what his price is yet. Everybody admits Nick kept a nice, quiet, lawful house, and still does. He sits in front of his place, in a chair in the sun, and watches the workmen building the foundation to the circular addition to the house where Gen. Washington slept, opposite. The Washington house is a little, narrow, two-story brick house—brick brought over from Holland, somebody says—and its chief possession used to be a picture of "George Washington and His Charger."

The house was the home of the Sherwood family, highly respected people. While the Father of His Country slept there, his "headquarters" were across the road in the Lyons house, also brick, with many cubbyholes and quaint angles, and to this William Crawford, the New York contractor who is rebuilding the village, is adding two L’s, a modern sleeping porch and colonade. Some of the other quaint old cottages that have not yet received even a coat of whitewash in the general renovation look on at the rejuvenation of Washington’s Headquarters with bleak and stunned surprise. Across on the other corner of Liberty street—named for the Liberty Boys of the Revolution when they came home to rest after the Battle of White Plains—stands in prim delicately tinted stucco, the pretty Community House.

The old-fashioned half door with its quaint knocker, in the Washington house, stands open these days and Mrs. Mary F. Seccombe’s pet kitten "Little Somebody," sits on the top of the lower half and purrs while mortar is mixed in the street for more houses. A big old manse further toward the river, overlooking the crumbling limekilns and the decaying dock, has been torn out inside and is reappearing as a modern dwelling with all improvements.

Up on the top of Quarry Hill rises the tower of Calvary Chapel, the hamlet’s one church. A little beyond, down to the river, winds the narrow gauge railroad which carries the lime rock from the quarry to the river. The quarry is an immense white hole 800 feet long, 500 feet wide and 150 feet deep where lime rock has been taken out for 100 years or so. The early Silurian limestone crystalized into fair marble, is interesting to geologists for containing tremolite, actinolite, traces of native silver, cerusite, copper pyrites and other minerals.

Some of the villagers are rather indignant at the way they have been routed out of peaceful sleep by the carpenters and masons of Mr. Vanderlip. They look with surprised horror at the advent of news photographers, who insist that the village is news. Nothing ever happened there before which was news, and when some photographer takes the picture of Mrs. Seccombe’s kitten, "Little Somebody," and bears it off in triumph, they do not understand. No Sparta cat was ever photographed for the papers before.

Grandma Trathen, over 80, beloved by everybody in the hamlet, who has brought up her children, grandchildren and great grandchildren in Sparta, and after the renovation began moved into a tiny little cottage near her descendants, seems interested in the renovation of the village and watches it with beaming eyes.

At last there is excitement and something happening in Sparta. She is a dear old lady, and the younger women wonder, a little sadly, if grandma will recognize the hamlet after it is made over. Grandma knows the history of the hamlet better than anybody else, now that Mrs. Mary Shortell, widow of James, who had lived there most of her life, has joined her husband "over there."

Some of the villagers seem pleased at the renovation. The only ones not deeply stirred one way or the other are those who are sleeping so calmly over the hill on the Revolutionary Road in the little cemetery. They don’t seem to mind, though nothing has stirred their home village so since a round of shot from a British man o’ war in the river screamed over the village during the Revolution and buried itself in a stone wall in this same little cemetery. The villagers point out the great hole in the wall with a little touch of pride, even now.

"I don’t know," said Mrs. Andrew J. Robinson, who lives at the corner of Revolutionary Road, "when anything has happened in Sparta so exciting. It has been a quiet, peaceful, sweet little village as long as I can remember, and I lived here when I was a little girl, and used to go up to the Community House, as they call it now, to see Mr. Holden play Santa Claus. One thing I wish you’d print. The stories about Sparta being a sanctuary for escaped Sing Sing convicts in the old days is all false. (This was a fake sensation story of a local yellow journal.)

"When anybody got out of Sing Sing then, as now, he put as many miles as he could between himself and the prison. He never tarried here. I have known years to go by in this hamlet without as much excitement as somebody’s horse running away. The people have always been nice, quiet country farmers and a few honest laborers on the railroad and in the quarry. Nobody ever did anything to get the village into the papers. We just lived quiet, happy lives."

For more information, see the History of Sparta pages on this site: